Thoughts on STM

The two major modes of concurrent programming are explicit locks and message passing.

Explicit locks are familiar from, well, everywhere. Most languages either has primitive locks built in (Java's monitors) or offer them through a library (C with pthreads).

Message passing is usually exemplified by Erlang (Actor Model), but Golang (CSP) is a more recent language that supports it natively.

But there's a third, less familiar mode known as Software Transactional Memory (STM). Available in many languages and actively promoted in Haskell and Clojure, it's the secret sauce behind Rich Hickey's epic ant colony demo.

So is STM in Haskell and Clojure the same thing (hint: no), and how does it work?

Compare And Swap

Transactional Memory was originally hardware based and required custom wiring in the CPU. But in 1995 Nir Shavit and Dan Touitou published Software Transactional Memory. In the paper they argued that multi-processors are the future, and that non-blocking1 algorithms are the only way to make full use of them.

Many non-blocking algorithms had been published in the early '90s, but unfortunately they depended on instructions that real CPUs did not support, like the k-word CAS. Single-word CAS was supported, but there was no obvious way to extend it.

Shavit and Touitou found a way to do it. They designed a software version of Transactional Memory and showed how it could be used to implement a k-word CAS. It would be slower, but it would allow the non-blocking algorithms to run on existing hardware. 2

Transactions

When we think of transactions, we think of databases. This is a terrible analogy.3

A better mental model for a transactional memory is a small number of machine words organised in an array. The program can modify this array as if it was regular memory:

swap_addrs_0_and_1() {

atomic {

a = read m[0]

b = read m[1]

write m[0], b

write m[1], a

}

}The atomic keyword denotes the start of a transaction. When the block ends, the transaction commits. Transactions appear to run serially with respect to each other.4 Another transaction that reads m[0] and m[1] will see either the original or the swapped values, but never an intermediate state.

Seralizable isolation is a strong guarantee. There are several ways to enforce it.

A naive implementation could hold a global lock for the duration of the transaction. The memory could then be just a chunk of DRAM, and the commit operation would do nothing apart from releasing the lock. This provides serialization at the cost of zero concurrency.

Any solution that wants to do better needs to allow more than one transaction to run in parallell. That involves some complications.

- It must be able to detect incompatible memory access, i.e. collisions.

- If collisions result in a failed transaction, there must be a recovery mechanism.

- To ensure liveness, at least one transaction must always be guaranteed to make progress. This could be as simple as ordering the transactions by their start time and resolving collisions by letting the earlier transaction win.

Let's look at some real implementations.

Concurrent Haskell

Haskell is an enviable language. It seems to thrive when faced with a good challenge. In the lazy, functional domain, where seemingly simple ideas like state and ordering of operations can be awkward to deal with, concurrency seems like an especially thorny problem.

To my great surprise, Composable Memory Transactions from 2005 shows that Haskell makes for a particularly beautiful implementation language. I will keep my summary short, because the paper itself is quite readable. Beyond that, you will find documentation on the wiki, including an entire book chapter written by Simon Peyton Jones for Beautiful Code. It is a gentle, yet excellent introduction.

In concurrent Haskell, the atomically keyword delimits a transaction. The transactional memory is not an array, but is defined by a set of transactional variables of type TVar. The first time a TVar is read within a transaction, its value is copied to a local cache known as the transaction log. Subsequent reads and writes are directed towards the log, and are not visible to other transactions.

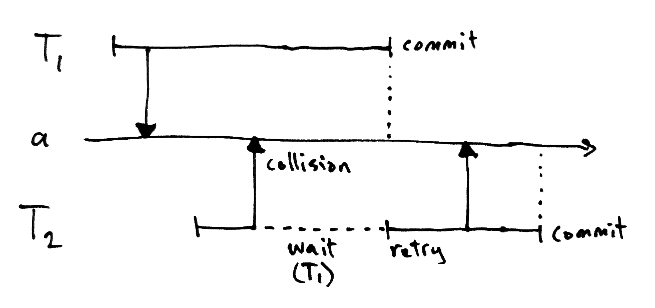

Haskell's STM uses Optimistic Concurrency Control. It starts transactions in parallell, hoping for the best. This provides for excellent concurrency when they do not collide.

At commit time, the values in the transaction log are compared to the current values of the TVars. If they match, the transaction succeeds and the entire log is flushed atomically, using either locking or some architecture-specific mechanism like k-word CAS. 5

A mismatch means that some other transaction commited first. This is resolved by aborting the transaction and retrying. This is safe to do, because Haskell's type system guarantees that there are no side effects in the atomically block.

This guarantee is a major advantage. It spares the programmer from worrying about the effects of (sporadic) retries. The type system will also disallow any interaction with a TVar from outside a transaction.

What if all the TVars match except one that was simply read?

It may be tempting to allow such a transaction to commit, but doing so would compromise the serializability requirement. More on this later. I believe Haskell's algorithm guarantees true serializable isolation, but I have not actually verified this in GHC.

This synergy between the type system and transactions was completely unexpected to me. I'm sure it took a great deal of brilliance to hammer it out. And I have not even mentioned that Haskell's transactions are composable - a main result in the paper.

Clojure's Refs

Clojure's take on STM is more pragmatic, but not without its own share of brilliance. It's an example of Multiversion Concurrency Control. If you have not been exposed to MVCC before, you're in for a surprise.

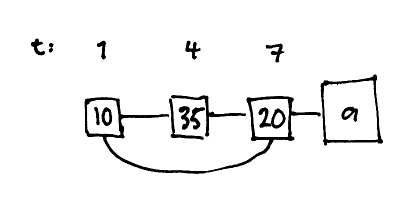

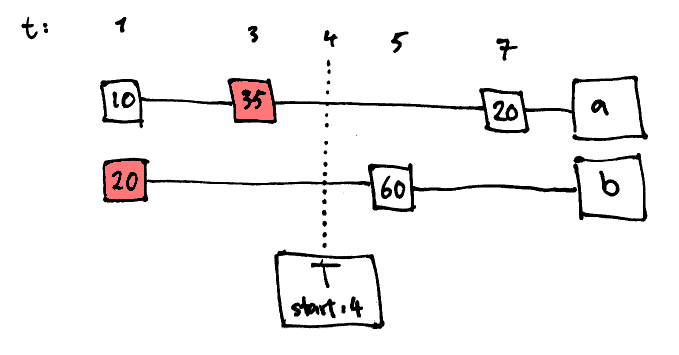

The dosync macro defines a transaction, while the shared memory is defined by the set of refs that are accessed. A ref is a wrapper around a history of values, implemented as a doubly linked list. Each node contains a value and a write point, which is a unique timestamp6.

Transactions may fail, in which case they are automatically retried, like in Concurrent Haskell. There is no protection against side effects (beware!).

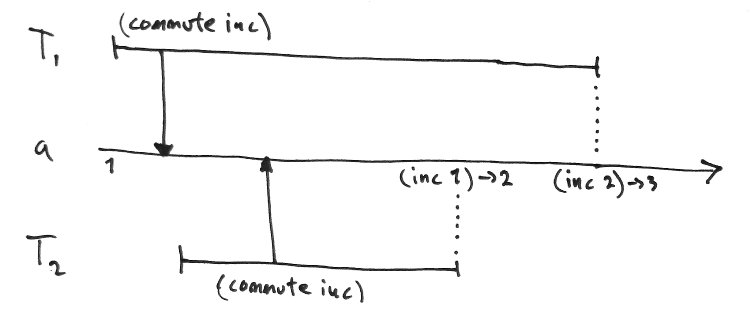

When a transaction begins, its start point is recorded and the transaction is published in a ThreadLocal, so that all reads and writes can be delegated through it. This allows for book-keeping, and for the transaction to retry early if it becomes doomed to fail.

Read

Reading from a ref involves walking down its history list until a value is found that predates the transaction's starting point. The effect of this is that a transaction always observes a consistent snapshot of the transactional memory at the time when the transaction started.

Given the snapshot mechanism, it may seem like a read operation cannot fail. But the history lists are not of infinite length. By default they grow dynamically up to length 10. If a transaction cannot find a value with an early enough write point, it retries with an updated start point.

The limited history length is one reason why combining long and short transactions can result in retries. The history sizes (min and max) can be customized per ref to mitigate such issues.

Write

Writes to a ref are stored locally pending commit, just like in Haskell. In addition, the ref records the fact that it is being updated. So when a second transaction comes along and tries to write, the conflict can be detected immediately.

A write collision is resolved in one of two ways. If the second transaction started recently, it gives up, waits for the first transaction to end (successfully or not) and then retries. But in case it has been running for some appreciable time - BARGE_WAIT_NANOS - the starting points of the two transactions are compared and the oldest transaction wins. This helps protect long transactions from being starved by short ones.

Here's an interesting case of write collision: Consider two transactions that update the same two refs in opposite order.

(let [a (ref 0) b (ref 0)]

(dorun (pcalls

#(dosync (ref-set a 1) (ref-set b 1))

#(dosync (ref-set b 1) (ref-set a 1)))))

^^^^^^^^^^^If the transactions were to execute with perfect parallelism, instruction for instruction, they would both detect a write conflict on the second ref-set. This would send them into an infinite retry loop. Of course, in the real world either one would eventually manage to give up and stop before the other detects a write conflict, which would unstick them both.

Apart from ref-set there are two other write operations: alter and commute. Alter just offers an idiomatic way to update a ref based on its current value. These two lines both increment x:

(ref-set x (inc @x))

(alter x inc)Commute is interesting. It's used like alter but does not cause write collisions. The idea is that if two transactions both alter a ref using a commutative function, the result is the same regardless of who commits first. Imagine what happens if every transaction needs to update a shared counter:

(dosync

...

(alter global-transaction-counter inc))The result would be lots of write collisions and retries. Use commute here to allow for more concurrency. Just make sure the function really is commutative!

Commit

The commit logic makes up the bulk of the LockingTransaction class. This class and Ref together make up the STM implementation.

Commiting is straightforward if there are no collisions. The set of refs that were read, updated, ensured (see below) or commuted are known at this point. The transaction must lock all of them except the reads, and then execute the pending updates atomically.

The tricky bit is to handle retries correctly. It's done by throwing and catching a special Java Error. If a (ref-set) throws, the stack is unwound to the top of the dosync block, skipping the rest of the transaction.

This is safe to do as long as the transaction contains no side effects. Again, that's up to you to ensure. And please avoid catching Throwable inside a transaction, unless you want a truly demonic bug on your hands.

Snapshot Isolation

Finally some notes on isolation guarantees.

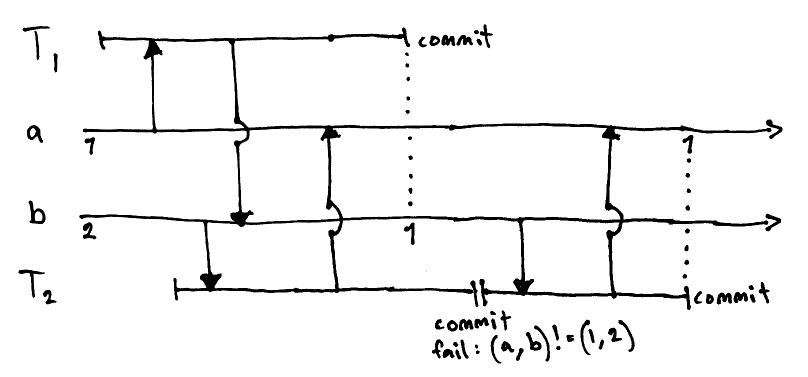

The program below starts with two refs [a b] with values [1 2] and runs two transactions in parallel. The first one moves the value of a to b, and the second does the opposite. With true serial isolation there are two possible results: [1 1] or [2 2], depending on which transaction runs first.

However, by inserting a delay, we consistently get a third result. What's going on?

(defn move [src dst]

(dosync

(let [tmp @src]

(Thread/sleep 500) ; artifical delay

(ref-set dst tmp))))

(defn ws []

(let [a (ref 1) b (ref 2)]

(dorun (pcalls #(move a b) #(move b a)))

[@a @b]))

user=> (util/ws)

[2 1]Clojure's STM does not in fact guarantee serializable isolation, and the documentation is very clear on this. What it does guarantee is snapshot isolation.

Snapshot isolation ensures that when you observe a set of values from a transaction, they form a consistent view of the world. In other words, you won't see any partially commited transactions. But your transaction will not fail merely because you observed a value that is no longer current. Unlike in Haskell, there is no CAS validation of the read set.

This explains the behaviour we saw. In isolation terms it is called write skew, and it is a problem if the program's correctness depends on serializability. The burden is on you to decide when it does.

Now that we're aware of write skew, what can we do about it? An obvious workaround is to include a seemingly pointless

(ref-set src @src)to transform write skew into a write collision. Clojure also provides

(ensure src)which has the same effect and makes the intent clear. Actually the effect is not exactly the same. Unlike ref-set, ensure unconditionally prevents other transactions from writing to the ref. So even a transaction that would have won in a write collision will lose against ensure.

The reason for this oddity is to avoid false collisions between two ensures, which would be possible if they were handled like writes. This optimization could end up saving us many pointless retries.

Conclusions

The STMs in Haskell and Clojure are not identical. Haskell provides stronger isolation and an emphasis on safety.

A read-only Clojure transaction can fail, if the history buffer overflows, or if ensure is used.

Keep on your toes and watch out for write skew!

Why bother to learn about STM at all? Apart from broadening your horizons, STM could be the concurrency mode of the future. It provides the same sort of performance vs. peace of mind tradeoff for concurrency as the garbage collector does for memory allocation.

If we choose a non-pure language, there's the problem of side effects inside transactions to deal with. But no deadlocks.

-

Consider a non-blocking tree. One thread could insert a node while another scans through some unrelated branch. This could allow for more concurrency than if writers require exclusive access to the entire tree. Writing a correct non-blocking tree turns out to be hard. ↩

-

I would love to explain the algorithm, but it's too complicated for me. Also, I should point out that it is based on the LL/SC instruction, which was available on the PowerPC in 1995, but not on x86 (and still isn't). ↩

-

In terms of ACID properties, software transactional memory is only concerned with Atomicity and Isolation. There are no tables in STM. The size of your typical transactional memory is measured in bytes, not in gigabytes. ↩

-

The isolation level in a real STM implementation may or may not be fully serializable, as we will see. Just like with databases, make sure you know what guarantees you are getting! ↩

-

That's right, Haskell can use k-word CAS to implement its STM, where the original paper did the opposite. ↩

-

Actually a point is a

longvalue from an increasing sequence, but it behaves like a timestamp. It defines a total order on transactions and ref values. ↩