Know Thy Shell

Bash, the Bourne-Again Shell, used to make me uneasy. I avoided it, like someone with cynophobia might avoid walking past the neighbors house because the neighbor's dog barks at strangers. Irrational fear, plain and simple. I had no idea how to fix this, so I tried something new; I read through the Bash manual like a book, all 90 odd pages of it, over several weeks. This had some unexpected results.

The main result? I am now a huge fan of Bash. The shell is still an odd beast in some ways. But we have established a few house rules. Now me and Bash are best friends.

This is the long and sprawling story of how I came to love my shell, and then moved on to dump it for it's prettier cousin. If all you want are the quick hits, I wrote down my favorite Bash tips separately.

Fun in 640k

In the early 1990's I was a proud MSDOS user. Hacking config.sys and

autoexec.bat to free up memory for games was the first programming-like

activity I experienced.

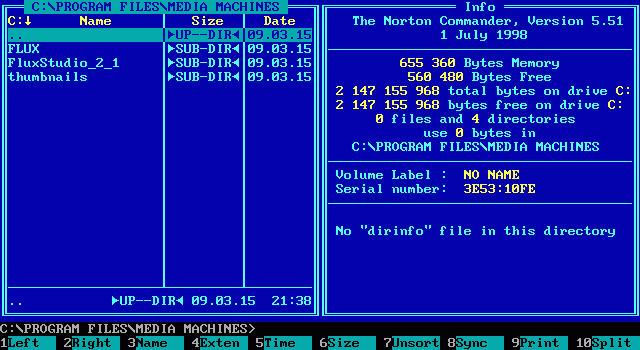

The DOS shell, command.com, was a shockingly primitive shell by Unix

standards. But that didn't matter, because we had Norton Commander. It

is an awesome text-based file explorer. For the use cases I cared about,

which was copying files around and editing config files, it set a bar in

ease-of-use that has still not been cleared.

Linux Beginnings

Meanwhile, Linux was gaining popularity. Slackware was a great first Linux

experience; a whole distribution compiled from nothing but loose ends. You

installed the base system, and 30 minutes later you were compiling a kernel.

The default shell was Bash. It looked sorta like command.com to me, except

the commands were all different.

Linux was a huge leap forward compared do MSDOS. It ran in 32-bit protected

mode. It had native TCP/IP networking. But Bash felt like an almost as great

leap backwards from Norton Commander. Miguel de Icaza (of later Gnome and

Mono fame) seemed to agree, because he was already working on a port called

midnight commander. The port was great, but the keyboard shortcuts were

not quite the same, and a lot of Norton Commander's usability advantage was in

the keyboard shortcuts. So for exploring /etc/rc.d on my Slackware system I

mainly used Bash. I read so many HOWTO's and man pages, from Samba to BIND,

but somehow it never occured to me to properly learn about the shell.

After 15 years of running a home server on Linux, I had picked up a bunch of tips and tricks, but some of the shell concepts had passed completely over my head.

Learning Bash the Hard Way

Is it nuts to read a 90 page manual for something you use for maybe 2 minutes a day? First, what if I told you that you could transform those 2 minutes from a pain to something to look forward to? Just like sharpening the kitchen knife can make cooking fun again, getting to know your shell makes it fun to play around at the prompt. Or at least much less annoying.

Second, the shell is a historical curiosity. Any program that stays around for 20 years without changing much, either got something right, or is impossible to replace for legacy reasons.

Bash is also one of those programs where, if you don't know it well, you will end up emulating some of its features anyway, just inefficiently. Like if you know about input / output redirection but not pipes, you might "pipe" programs by storing output in a temporary file. Or write lots of single-line shell scripts instead of using the history search feature.

You can do what I did and pick up a clever trick at a time from one of thousands of blog posts that sing Bash's praise, hoping that eventually they will coalesce into an understanding. But that's inefficient. In my opinion, for the basic concepts, you are better off learning them from the manual.

So what are those concepts? The rest of this post is an attempt to summarize them.

A Real Language

Bash may not be the prettiest programming language in the world. But it's a real language with a real grammar. There are conditionals, loops and functions. It is possible to write fairly structured shell scripts.

The grammar is packed densely onto a few pages at the start of the manual. It's impossible to understand all of it at first, because it uses many terms that are defined further on. Just make sure you understand what simple commands, pipelines and lists are, because those are the fundamental building block for most of the grammar. Yes, that means commands take the role of both statements and expressions in a C-like language.

In fact, Bash is best described as a domain specific language for running commands. Treating it as a language is the first step towards shell scripting.

Further reading: Shell Commands, Shell Functions, Bash Conditional Expressions

Shell Parameters

Shell parameters are a collective term for

- Positional parameters

- Special parameters

- Named parameters (variables)

The positional parameters contain the command line arguments that were passed

to a script. They are accessed with $0, $1, etc.

Special parameters is where Bash stores things like $?, the exit status of the

previous command.

Named parameters are NAME=value pairs. They are also called variables, and

are used to hold values e.g. inside a script. An example would be $BASHPID,

the process id of bash.

The environment is also a bunch of NAME=value pairs that contain runtime

configuration for programs (e.g. $HOME or $CLASSPATH). The environment is

an OS feature, not specific to the shell. In Bash, shell parameters can be

exported, which means they are promoted to the environment.

The distinction between parameters and the environment had me confused

for a long time. It is the key to understanding when to use export.

Further reading: Environment, Shell Parameters

Execution Environment

The execution environment is the state of bash, and consists of all the current shell parameters, functions, aliases, open files and shell options.

This section of the manual explains how programs are started and what parts of the environment they inherit. Just like the grammar, it will be hard to digest to begin with, but once you get through the whole manual, this is going to be very familiar.

Further reading: Executing Commands

Redirection

The pipe operator is one example of redirection. It is a key mechanism in the Unix philosophy of many small tools working together.

But redirections in Bash can do much more. In fact, they constitute a small sub-language for manipulating file descriptors. Learn this sublanguage. It's pretty simple. If you are new to file descriptors, there is a great post here with some images that will make things clear.

Further reading: Redirections

Expansion

Filename expansion is by far the most common type of expansion. It is what

turns *.txt into a list of filenames.

You should know about the other types of expansion as well, so you understand

what's going on when you activate them by mistake. It's easier to remember

that {} must be quoted if you know what they do (brace expansion).

Between pipes, command substitution and process substitution and here docs, temporary files are rarely needed to make commands work together.

Further reading: Shell Expansions, History Expansion

Job Control

The shell has it's built-in multitasking support. This may seen silly if you're on a graphical desktop, since you could just launch multiple terminals, ssh sessions or whatever, but it is occasionally useful.

Just a word of caution. If you want to understand job control for real, you need to lean a few things about signals and terminals as well, which might be more trouble than you bargained for.

Further reading: Job Control

History

The history facility remembers your commands so you don't have to. Whole

commands or parts of commands can be recalled with the history expansion

operator (!). Even more useful is the interactive history search, which is

part of the command line editor.

Further reading: History, Searching for Commands in the History

Command Line Editing

Bash uses the readline library for editing, with its Emacs-inspired default bindings (a binding is readline-speak for keyboard shortcut). Readline has tons of predefined bindings, and a separate man page that lists all of them. If you take the time to read through them all, you will almost certainly find some useful stuff. It's up to you how much you want to memorize.

Further reading: Command Line Editing, Bindable Readline Commands

Builtin Commands

Not really a concept, but a bunch of internal Bash commands. You know the most

important of these already, like cd and . (dot a.k.a. source).

Further reading: Shell Builtin Commands

Enlightenment?

After a read-through you'll navigate the man page with confidence. Where do you go from here?

Paradoxically, once you know what Bash can do, you might be tempted to shop

around for something even fancier. The natural upgrade path is the Z

Shell, or zsh, which is what I'm using. It works 95% fine as a drop-in

replacement to Bash, which means you can learn about its features as you go.

Does zsh have a man page? It has several, actually, but man zshall will

show them combined into one large blob.

$ man bash | wc -l

5459

$ man zshall | wc -l

26390Ouch. That's around 430 pages. I wonder if the extra features are worth it ...